The end of the web? Goodbye HTML, hello AIDI!

People are already turning to AI to answer questions, compare products, and make decisions in seconds.

That shift exposes a fundamental problem: the web’s underlying structure was never built for machines.

As AI agents mature, the way information is delivered – and the need for traditional webpages – could change dramatically.

Disruption is normal – even when we don’t see it coming

The idea that the web as we know it could end, which I mentioned during a live OXD podcast in Salzburg, drew reactions ranging from thoughtful to angry.

Someone even insisted, “The web will always be there.”

But anyone paying attention knows that “always” and “never” rarely hold up in technology.

History shows that nothing technological is permanent.

When fundamental shifts happen, we call them disruptions because the impact becomes undeniable only in hindsight.

Back on Aug. 6, 1991, who could have imagined that Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web would upend the world?

The same pattern has repeated for centuries.

The steam engine, the loom, the printing press, the car, smartphones, and the move from analog to digital were all dismissed at first as too expensive, too slow, or too complicated.

People pointed to existing solutions and assumed they would endure.

We also tend to judge new technologies too early. We compare immature, unoptimized versions to mature systems we’ve relied on for years.

What we rarely do is imagine the new technology in its fully developed state – and only then make a fair comparison.

That habit clouds our view of the future.

What buying a smartwatch reveals about the web’s limits

Where do you go for information when you want to buy a smartwatch?

Often, it’s the manufacturers, retailers, or websites Google returns for your search terms.

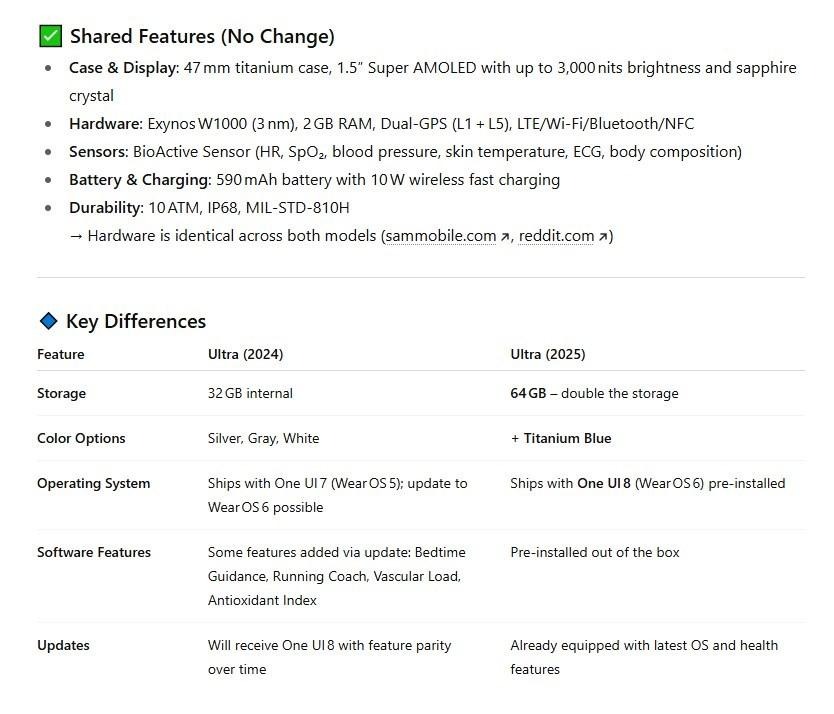

I want to know the exact differences between the Samsung Galaxy Watch8, Classic, and Ultra, and whether the price gap is justified for what I need.

Can I find that at Samsung? Probably not.

Each product has its own page and is described as “super.”

I end up taking notes by hand just to compare basic details.

I wonder what distinguishes a fabric band from an athleisure band, what a 3nm processor does for me, or what One UI even is.

To understand the sleep-monitoring features, I have to copy the text and translate it into German by a tool because Samsung used an English explanation.

There is a “compare” function in the shop, but it doesn’t help much. It often raises more questions than it answers.

For example, doesn’t the more expensive model have a running coach?

Yes, but the marketing team highlighted other differences, and “quick release” or “timeless design” seemed more important to list.

And what do “A2DP, AVRCP, HFP, HSP” or “16M” mean in terms of color depth?

Is “Super AMOLED” really super?

Comparing one of these watches with a model from another brand is even harder.

That’s when you usually start googling and end up on SEO-driven pages that compare everything with everything else, claim to test every product, and ultimately push you toward a paid affiliate link.

How asking AI exposes the web’s weaknesses

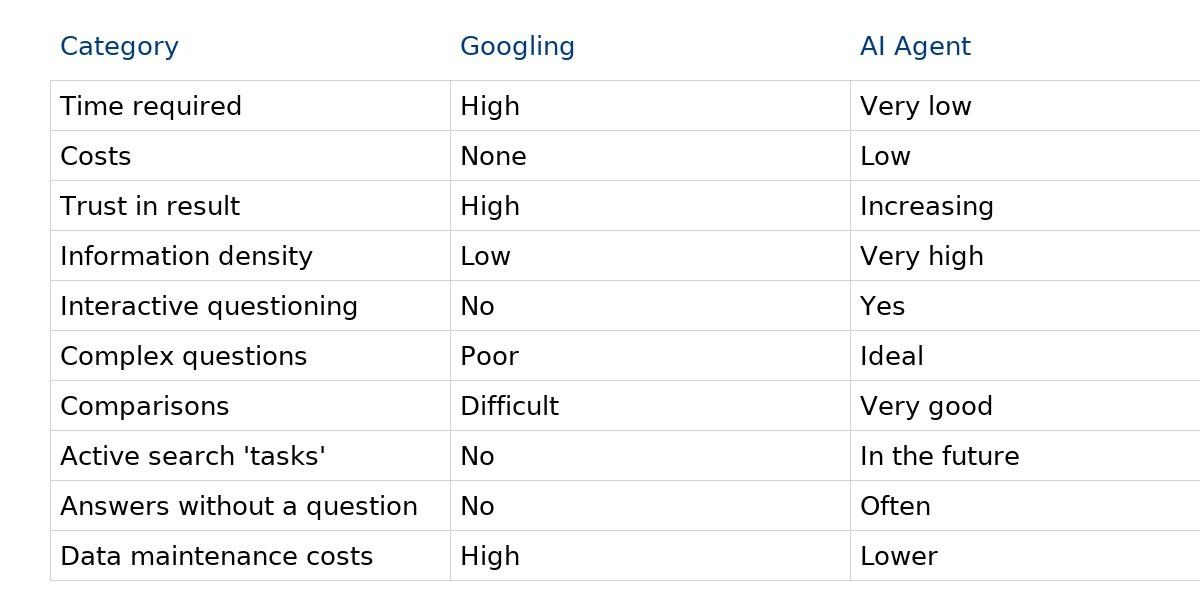

To get a full overview, I need a lot of time – often more than an hour.

On Google, I have to vary my search phrases and click through each result individually.

But asking ChatGPT, “What are the main differences between the Galaxy Watch8, Watch8 Classic, and Ultra?” gives me an overview of similarities, differences, and an assessment within four seconds.

As shown below, I’m even prompted to compare price and benefits.

If I ask follow-up questions, even specific ones, I get clear answers.

And if I want to know how these models differ from an Apple smartwatch, that’s no problem.

Open questions are quickly explained in the dialogue, and I’m given ideas I hadn’t even considered.

“Should I check whether all the watch’s functions work with your phone?”

ChatGPT asks. “Yes, it’s a Pixel phone.” I’m immediately told that some functions, such as blood pressure measurement, won’t work unless I’m using a Samsung phone.

This small, random example shows how time-consuming and often inadequate web research can be.

Manufacturers and retailers present products in a way that they think we want to see them.

But we usually have more questions and often want one thing above all: to compare.

We’re delta thinkers – we want to know the difference.

On the other hand, suppliers tend to present products in a singular, non-comparable way.

If a product lacks something, it’s better left unsaid or made as opaque as possible. That’s understandable, but it doesn’t help us.

Take a break now

Stop reading this article and use your AI of choice to search for explanations, comparisons, and benefits of any products or services.

If you haven’t been doing this more often lately, try it now. You’ll be amazed at how detailed and close the answers get to what you actually want to know – in seconds.

If you’re unsure whether the answers on certain topics come from reliable sources, simply include that in your prompts:

- “Only search designated expert sites.”

- “Only use well-known institutions.”

- “Give me all sources.”

- And so on.

The latest version of Google’s Gemini signs off politely when you request in-depth research and then works on it for up to 15 minutes.

You’ll get a message when the answer is ready, often in the form of a report of up to 50 pages generated just for you.

Practically nothing is left unanswered.

School and university students use this mode to produce almost finished assignments or seminar papers, needing only to add their names.

Whether that is good for learning is another question, but one thing is certain: it saves a lot of time.

And unfortunately, the results are often better than what someone might produce on their own.

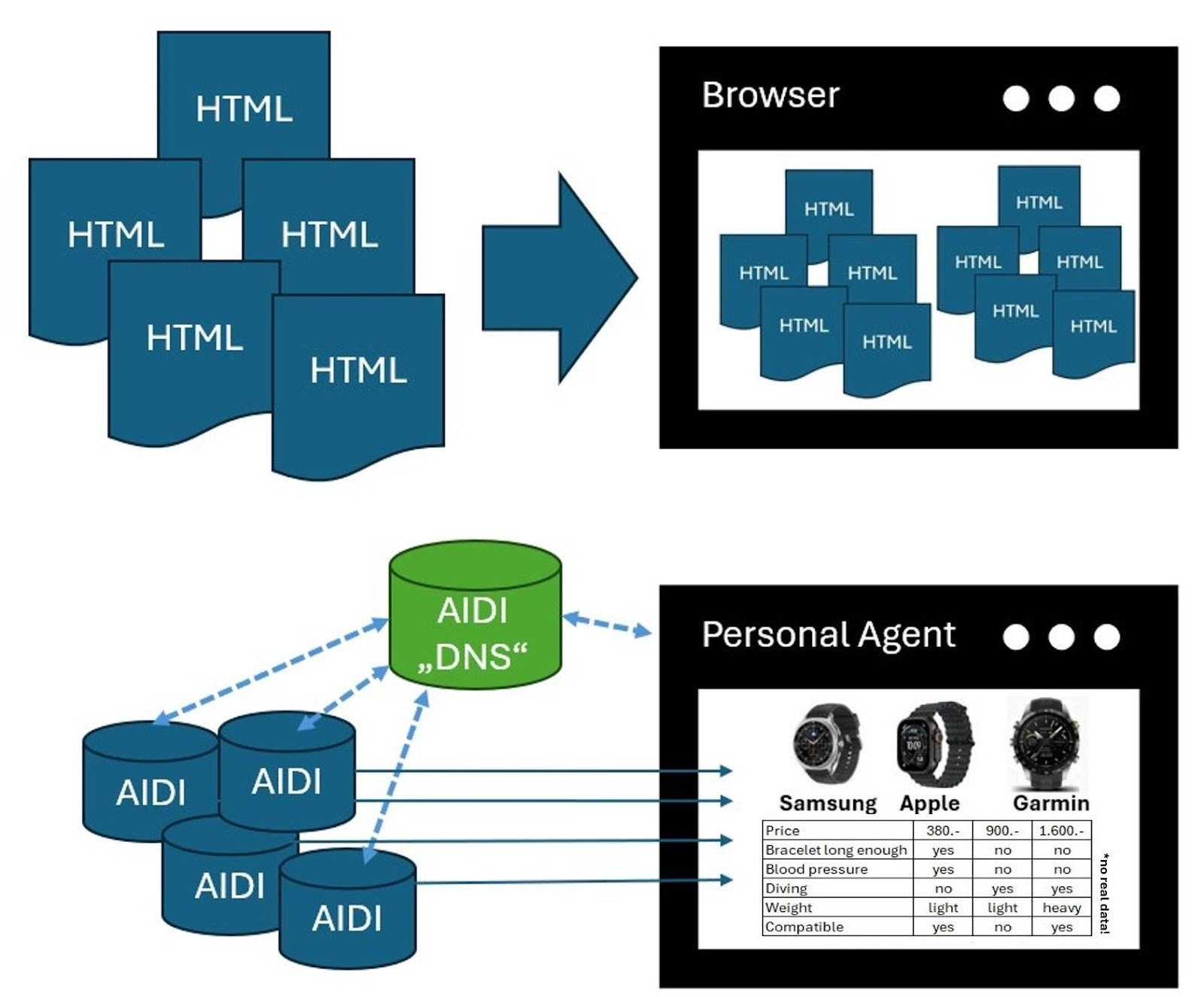

HTML is a markup language – for humans

We use HTML to display text and images flexibly in a browser. It determines where something appears and how it is shown.

That has been useful for humans since the start of the web. In recent years, though, a workaround has been added for a growing problem.

When a product page says “€9.99,” we know that’s the price. Our brains assign meaning automatically.

And if a number like “90409” appears before a place name, we recognize it as a postal code.

But none of that meaning exists in the HTML code. The code defines formatting, not semantics.

As websites are increasingly analyzed by machines, including Google, this became a challenge.

How does a machine know that “9.95” is a price? And does that price include or exclude VAT?

The solution was structured data – markup that sits invisibly inside HTML so machines can “understand” the meaning of words or numbers.

But only larger companies and shops tend to use it. Most of the web still doesn’t.

Depending on the study, only 10% to 30% of sites use structured data at all. Bad luck for the machines – or for the website operators.

So even if we generously count structured data as part of HTML, the exact content of websites remains difficult for machines to interpret.

Google recognized early on that certain patterns, like a number matching a global location database, probably indicate a postal code.

Even gender can sometimes be inferred from first names if the mapping is clear. But the very need for these database “crutches” shows how much important meta information HTML simply does not convey.

In recent years, Google has worked hard to categorize and catalog the information it finds – think of the Knowledge Graph or author recognition.

For humans, the information on a page is usually clear and intuitive.

We can tell whether Mario Fischer wrote a text about a book or whether Mario Fischer is the author of the book being shown, often based on layout or phrasing.

For a machine, though, these are just sentences, words, and numbers.

AI still doesn’t care about that. It throws everything into the same pot and generates statistically plausible associations.

It doesn’t understand real meaning or real connections – at least not yet.

Thinking one or two steps ahead

Chatbots like ChatGPT and Gemini are not replacing websites yet.

The AI behind them still doesn’t understand context, as described above. It may seem like it does, but much of what we see is almost pure statistics.

So what will be possible in five years?

We’ve only had broadly usable AI for two to three years.

Think back to the first ChatGPT in November 2022 – and compare that to today.

We can now create images and moving videos, generate interview-style summaries, and even plan vacations with AI instead of reading hundreds of websites, reviews, and price pages.

All of this has happened in about 30 months, including the time it took Google and others to react to the GPT shock and expand their offerings.

So again: what will AI do in five years?

By then, we’ll likely all have personal AI assistants that could:

- Schedule appointments.

- Answer emails.

- Handle routine tasks.

- Search for information.

- Summarize it.

- Read it to us when we have time.

These personal agents won’t wait for prompts the way they do today but will work proactively in the background in a fully automated way.

The popular n8n platform already makes it possible to build early versions of these agent systems, although you still have to set them up yourself and think ahead.

If an email with an appointment request arrives, the system can categorize the sender, search your calendar for openings and reply with suggestions.

This is possible today, but it takes some tinkering.

In the future, personal agents will contact each other automatically and negotiate a meeting time in a fraction of a second.

When the appointment arrives, the user will get a brief or detailed briefing – whatever they prefer – along with all the information they need.

Scenarios like this no longer sound utopian and are considered entirely feasible, if that’s the direction we choose.

Get the newsletter search marketers rely on.

See terms.

From stochastic parrot to domain AIDI

This brings us to a crucial point.

Today’s chatbots respond based on statistical word probabilities. They’re trained on whatever texts could be gathered – books, the web, and more.

This approach isn’t accurate or reliable.

Information that doesn’t appear often in the training data is hallucinated or estimated. Our future agents will likely not be able to operate in this manner.

One solution already available is to have ChatGPT consult one or more websites before answering. That usually makes responses more reliable.

However, they would be far more reliable if the information retrieved in real time didn’t suffer from the interpretation problem described above.

For example, if it were clear what “Mario Fischer” means in a given text. Markup can help, but it’s rarely used.

Ideally, we’d use a data structure designed for machines. Instead of HTML text, a server would return data in a truly structured form – similar to a database query.

Rather than a wall of text, the AI would get a completed form: field labels and field values together, with content and meaning attached. Perfect!

If an AI received that structured form instead of an HTML page – which has to be stripped of code and styling – it could do far more with it and wouldn’t have to guess at meaning.

That’s also how an API works – an interface for exchanging machine-readable data.

Since we don’t have a term for an AI-first version of this, the interface for AI queries will be called AIDI here: an AI data interface.

Such an interface would make machine-driven data retrieval far easier and dramatically faster.

Two business models on the web: Selling and commission

There are many ways to earn money with a website, but they ultimately fall into two basic models.

- Selling goods or services.

- Earning money from traffic.

Traffic monetization is the classic publisher model, funded through advertising or click and sale commissions.

Transactional and informational searches are the two Google search types that historically drove strong revenue when paired with solid rankings.

However, with AI responses increasingly handling information-oriented questions, the “traffic” model has already been significantly impacted.

Google is accused of cutting off visits through AI Overviews.

Google denies it (for now), but that will likely turn out to be a white lie, just as it was with years of denying that traffic data was used for ranking.

The mistake critics make is again reflexively treating Google as the enemy.

The fact that sites earning money from information are, with few exceptions, likely a thing of the past is not Google’s fault but the rise of AI chatbots.

What should Google do – pretend AI doesn’t exist and keep showing 10 blue links for the next 20 years?

That Google’s AI, like others, was trained on these very sources is painful – and understandably so – for publishers.

But complaining doesn’t change the direction.

AI is here to stay, and people use it more every day.

As shown earlier with the smartwatch example, AI’s biggest advantage right now is time: you no longer have to read three, seven, or 20 websites to get the information you need.

No website writer can anticipate exactly what I want to know. I have to collect everything myself, and often end up frustrated.

ChatGPT and others give me exactly what I asked for.

If not, I refine the question, and the system remembers everything so far and builds on it.

Today, asking a chatbot often yields faster and better results than reading individual sites. Not always, but increasingly so.

That’s what’s killing information-oriented websites – not Google.

And Google knows it will ultimately win the AI game.

It has more than 25 years of experience evaluating website quality, domain reputation, trustworthiness, spam likelihood, and many other factors.

Competitors don’t have that.

OpenAI, Meta, Deepseek, Perplexity, and others may produce better answers at times, depending on preference.

However, they have no idea which websites truly contain the best information or where misleading content is published.

They treat all sources the same and use them equally for training.

And when they need to “research” live, they use Bing or quietly scrape Google results – still the highest-quality index.

Google’s next move, likely already underway, is a blend of an LLM with enrichment from trustworthy websites.

And because Google already has almost all web content broken into individual components inside its index, it doesn’t need to fetch pages. Internal API calls to its ranking systems are enough.

So, at least for information searches, AI bots can already replace much of what the web provides. You don’t need to be a prophet to see that getting even better soon.

That leaves transactional tasks. Once my bot helps me choose the right smartwatch, I still have to buy it. For simple orders, that’s easy.

However, if I’m concerned about delivery time, delivery date, discounts, product or manufacturer certifications, environmental factors, warranty, regional preferences, or even the logistics provider, the process becomes more challenging – for me and the bot.

I’d have to comb through many shops to find the best match.

How much weight do I give to price? Would I pay more for a retailer I trust to handle problems well?

Humans make these judgments automatically.

A personal agent could do this too if it knows my preferences.

But HTML, with its lack of machine-ready structure, becomes a barrier again.

That’s where domain AIDIs could help.

Instead of reading the visible HTML, my bot would extract all necessary information directly from a structured data interface.

Right now, this may sound like a pipe dream because such general interfaces don’t yet exist.

But all the data needed for them is already available from manufacturers and retailers – just spread across various systems, databases, and often still unstructured.

If a standards body started defining the data needed for purchases, momentum would build quickly.

As soon as the first AIs used these interfaces, the usual rush would begin: big players first, then everyone else.

Just look at today’s economic hype – everyone wants their company or products to show up in bot responses as fast as possible.

SEO, PPC, and social media are already slipping into the background.

The question everywhere is: How do I get AI to mention or recommend my company?

Once pressure mounts, new requirements are implemented quickly, sometimes so quickly that proportion and economic logic get tossed aside.

So whether companies will eventually feed data into these interfaces so bots can factor them into purchase decisions isn’t really a question. It’s only a matter of time.

And once the new sales channel exists, it will be used.

Silent commerce is already here

In the B2B sector, companies have long used interfaces like this through their ERP systems, such as SAP.

For decades, search programs at large manufacturers have quietly communicated with supplier systems, checking availability and negotiating delivery terms and prices – all digitally.

The only fundamental difference is that these systems “know” each other and share defined data structures and protocols.

EDIFACT, RosettaNet and IDoc are just a few examples.

A broader approach would require far more data and a data interface that is accessible to everyone.

So how would a personal agent find suppliers or retailers?

By using the same principle that lets websites be found through domain name servers (DNS).

You would register the address of your AIDI with a data provider.

That provider would determine the range of services or products you offer and replicate that information across redundant servers accessible to AIs.

If someone is looking for a pencil, these services would return the AIDI root addresses of all manufacturers and retailers that sell pencils.

Those addresses could then be used for tiered queries.

Are pencils available? If so, the bot could refine the query to include: HD strength, 25 pieces, next-day delivery, under $0.85, no shipping cost, sustainable wooden casing, and so on.

The examples here are simple and intentionally open-ended.

The goal is not to outline a complete framework with every requirement and level of complexity, but to illustrate the basic principle of this kind of silent commerce.

Even if it sounds enormous, it would be technically feasible.

People once said mobile phones were “impossible” because the whole country would need transmission masts – and everyone would need to own a phone for the system to make sense.

And as I often say, the person who bought the first fax machine was probably miserable. He had no one to fax.

And what about publishers?

A new architecture like AIDI could ultimately help everyone who previously earned money from informational content through advertising.

It would be possible to introduce a credit-based payment system for content requests made by AI agents – similar to how data retrieval is billed through APIs today.

The user or their AI agent could decide, case by case, whether a request is worth it and use the retrieved content in the generated response.

Payment could be handled directly by the bot through clearing systems, sparing users from today’s subscription forms.

Considering that many publishers already ask readers to pay monthly fees for digital news access, such an idea isn’t far-fetched.

The only change is that instead of a monthly flat rate, users would pay a few cents per retrieval.

That shifts operational costs from advertisers to users, but if the information is substantial and useful, why not?

The “free to read, but packed with banners and sticky video overlays” model was never popular and has long been a flaw in the web.

A personal agent can also completely replace the browser

Imagine a future in which websites still exist, but AIDIs exist alongside them.

My personal agent could access these interfaces to make purchases, first for simple items, then for more complex products and services.

If tradespeople kept networked digital calendars, booking a washing machine repair would be effortless.

Website and online shop usage would decline, and eventually, we might not need them at all.

A horror scenario? From today’s perspective, maybe.

But sales would continue. People would still buy things – just through a different channel.

Not through the web, but quietly and digitally through a personal agent.

The agent knows what the item is for and can include suitable alternatives. It might even do a better job than we could, since we work with limited and often outdated information.

This doesn’t mean “websites” as a consumption format have to disappear.

A personal agent could generate visually appealing pages from structured digital data whenever I want to read something. That could be on a phone, laptop, desktop, or through smart glasses.

But the information would no longer follow the visual form providers must use today. It would be organized according to my information needs.

These views would likely look very different from today’s chatbot text blocks.

Powerful AI could generate colorful, illustrated responses that feel nearly indistinguishable from a website – except that they are customized to me and drawn from multiple sources.

If I asked about a smartwatch, the output would show offers from several manufacturers, highlight the differences that matter to me, and even incorporate real-time generated videos.

What would the watch look like on my wrist?

Much more helpful than a plain “43 mm wide” line that doesn’t mean much.

Would supplying AIDIs with data cost less than producing full HTML pages? We can assume so.

Eliminating flowery descriptions alone removes the entire content-creation burden.

My AI would generate the human-readable text itself, in my preferred tone, with technical terms explained in a way I understand.

And if something still isn’t clear, I can ask directly – no need to search the web again for what “One UI” might mean.

It may sound like a strange thought experiment, but imagine we had skipped the web entirely.

There is no web. And now we have an increasingly capable AI in an app.

How would we handle commerce or information retrieval in a purely digital, agent-driven world?

We certainly wouldn’t invent HTML for that. Would we?

Will the web disappear?

Probably – at least in the long term.

There is little reason to keep maintaining large-scale web presences, and much more reason to expect that we’ll communicate with personal agents that become far more capable than they are today.

Using them is easier, faster, more personalized and simply more convenient.

And if technological history teaches us anything, it is that new systems always win when they are easier, cheaper (especially in terms of time), more personalized and more convenient.

Every board member or CEO has one or more human assistants who save them time.

Why shouldn’t we all have the same advantage if technology makes it possible?

When personalized AI systems and the necessary interfaces – AIDI – will actually arrive is still unknown. Predicting a timeline would be presumptuous.

Technological leaps appear suddenly and unexpectedly to most people.

When will the next startup, armed with enough venture capital, hit the market with a breakthrough?

And one question may be on your mind: If the web disappears, what will train future LLMs?

We can assume that everything available for training has already been used. And right now the web is filling rapidly with AI-generated content.

As I write this, one startup claims it can automatically generate up to 3,000 podcasts a week.

Who is going to consume all of that?

Machines would increasingly train on their own output, which makes little sense.

It is also unclear whether pure LLMs are a dead end and whether additional methods will be necessary. Many experts think so.

A human can learn to drive in a few weeks.

Compare that to the enormous effort behind autonomous driving and how long it is taking.

AI training may get a major boost once learning is no longer text-only but includes visual observation and active participation in the real world, as we’re beginning to see with robots.

A mobile, active machine with optical and tactile sensors – connected to a networked AI – would gain insights impossible to achieve through text alone.

One thing is certain: if the web does fade away, I’ll have a problem with the name of my trade journal, “Website Boosting,” in Germany.

Recent Comments